I spent the holiday season practicing my handwriting, which was… unexpected.

The reason why is that I got a Supernote Nomad, which was enough to warrant spending a pretty large chunk of time using it either exclusively or in tandem with my other devices.

Although it’s been only a couple of months, the part of me that initially pondered the Nomad as a “better notebook” is still reeling, since I feel like I’ve barely scratched the surface, but I’m getting ahead of myself.

Disclaimer: Supernote sent me the Nomad, a magnetic folio cover and a pen (for which I thank them), and this article follows my Review Policy.

One of the reasons I wanted to try the Nomad that will likely resonate with a lot of my readers is that I wanted a way to “unplug” while being able to capture my notes in some form of digital format.

The Internet is full of stories of people who are looking for less distracting devices, so I won’t add to those other to emphasize that I have also been pursuing ways to increase (or, rather, restore) my ability to focus on a few key things.

I have an unusual memory–neither photographic nor complete, but oddly specific. I rarely took notes in college, but I enjoy the focus that handwriting demands, even though I know I’m more efficient at long-form writing with a keyboard, whether in stream-of-consciousness mode or during iterative editing.

I’ve long known that proprioception and the hippocampus do help in forming associative memories that help me recall where and what I wrote, but the real challenge these days isn’t remembering what you wrote–it’s capturing it without distractions.

There is something about doing handwriting on computers that I find profoundly appealing–I used a Newton MessagePad and was obsessed about Palm devices (I still have a working Palm V somewhere), so being able to quickly scrawl out something on a distraction-free device and then re-work it on my Mac later is extremely attractive to me.

“Slow” times and being able to focus on painstakingly handwriting something (as well as the physical sensations of writing itself) are a luxury that seldom comes my way, so my take on the Nomad is likely to read a bit different from most other folk due to that.

But let’s look at the device itself.

Hardware

E-ink devices distinguish themselves more by their screen and other physical specs than CPU power or RAM, but I’ll go through them in a single go:

- Overall size and weight: 139×192×7mm, 266g

- 7.8” screen with 1404×1872@300 PPI, dubbed as a “Frontlight free” glass screen (yep, no lighting) with a soft film for writing.

- RK3566 Quad-Core 1.8 GHz CPU with 4GB RAM and 32 GB internal storage (plus internal microSD slot).

- 2700 mAh (replaceable!) battery.

- 1 USB-C (2.0/audio/OTG) port (on the top left).

- Wi-Fi (both 2.4 GHz and 5GHz, which is quite nice) and Bluetooth 5.0 (for keyboard support and audio playback, since there is no speaker)

The form factor effectively translates to an A6/iPad Mini-sized device (hence the moniker), making it highly portable and easy to carry around.

A fun fact here is that this is the same Rockchip CPU as the XPI-3566-Zero and the Radxa Zero 3W I am still testing, but running without any noticeable heat issues and integrated into an upgradeable motherboard–in fact, you can replace both the motherboard and the battery, which is a notable aspect.

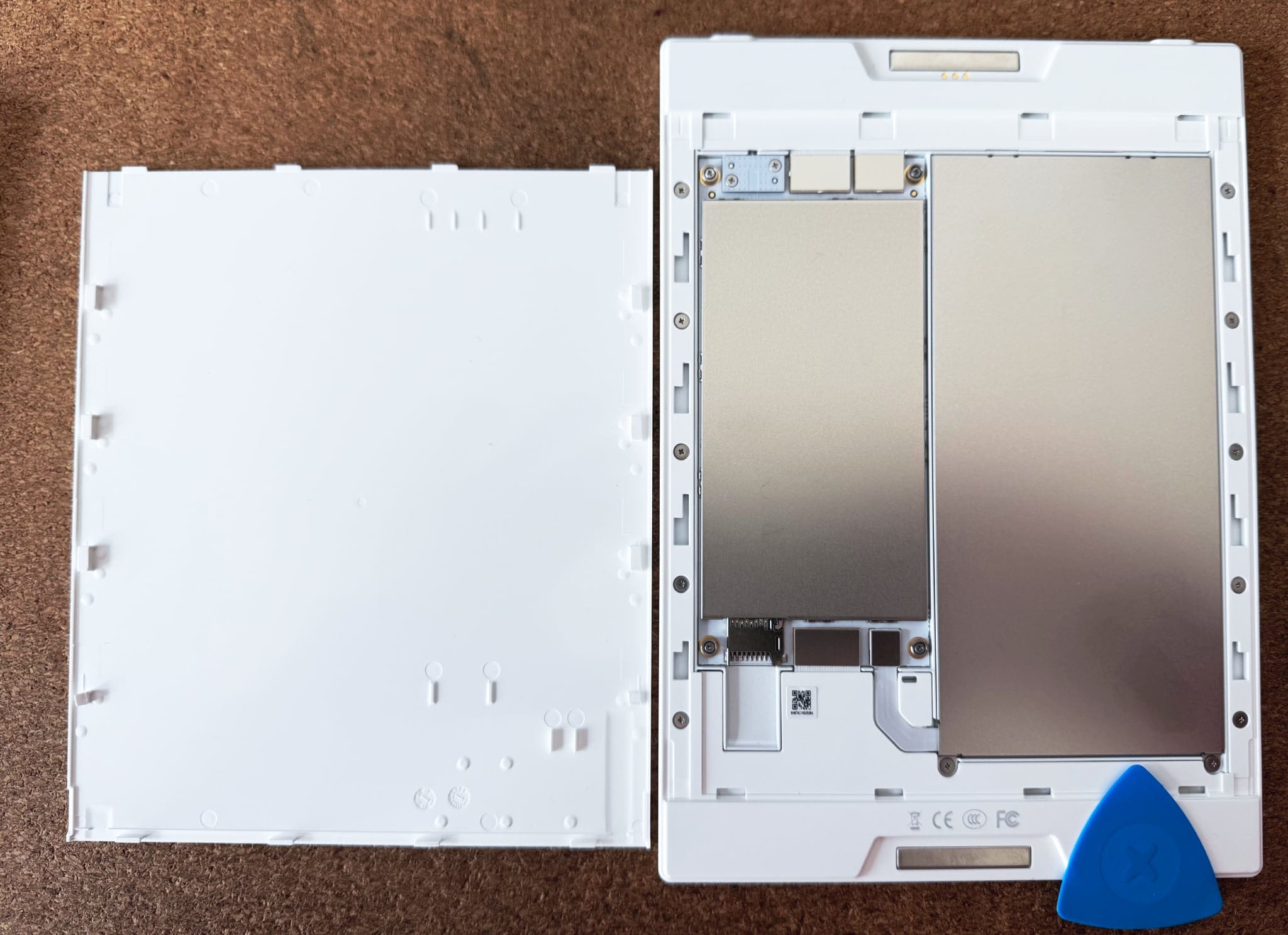

The Nomad can ship with a crystal clear back (which shows off its modularity and upgradeability, but is held with some unsightly screws) and a plain white back that is secured by molded clips (which require a deft touch to pop with a spudger or plastic blade).

I went for the less flashy option:

As far as I can tell, the newly released Manta (which launched roughly as I got this) is essentially the same thing with a larger screen, so you could theoretically “upgrade” or swap parts if you wanted to–this is a very pragmatic take on repairability, and is probably the first tablet (of any kind) I got in almost a decade that has a replaceable battery by design, which is enough to praise it even before I get to the software.

I suppose this hardware design ethos is also part of why they sell DIY kits for creating your own folio (with matching magnets to the Nomad’s) and a ballpoint “refill” with the EMR parts to build your own pen (which I find intriguing and might try out myself).

In the photo above you can see the (pretty strong) top and bottom magnets that the Nomad uses to clip to its folio. Regarding that, I picked the grey canvas option, which given the way pseudo-leathers feel in Winter felt like the right choice at the time–and I quite like it in reality. Even though I know it will eventually get coffee stains (or worse), it looks and feels very nice to the touch, as well as having a quite substantial pen loop.

Pen and Screen

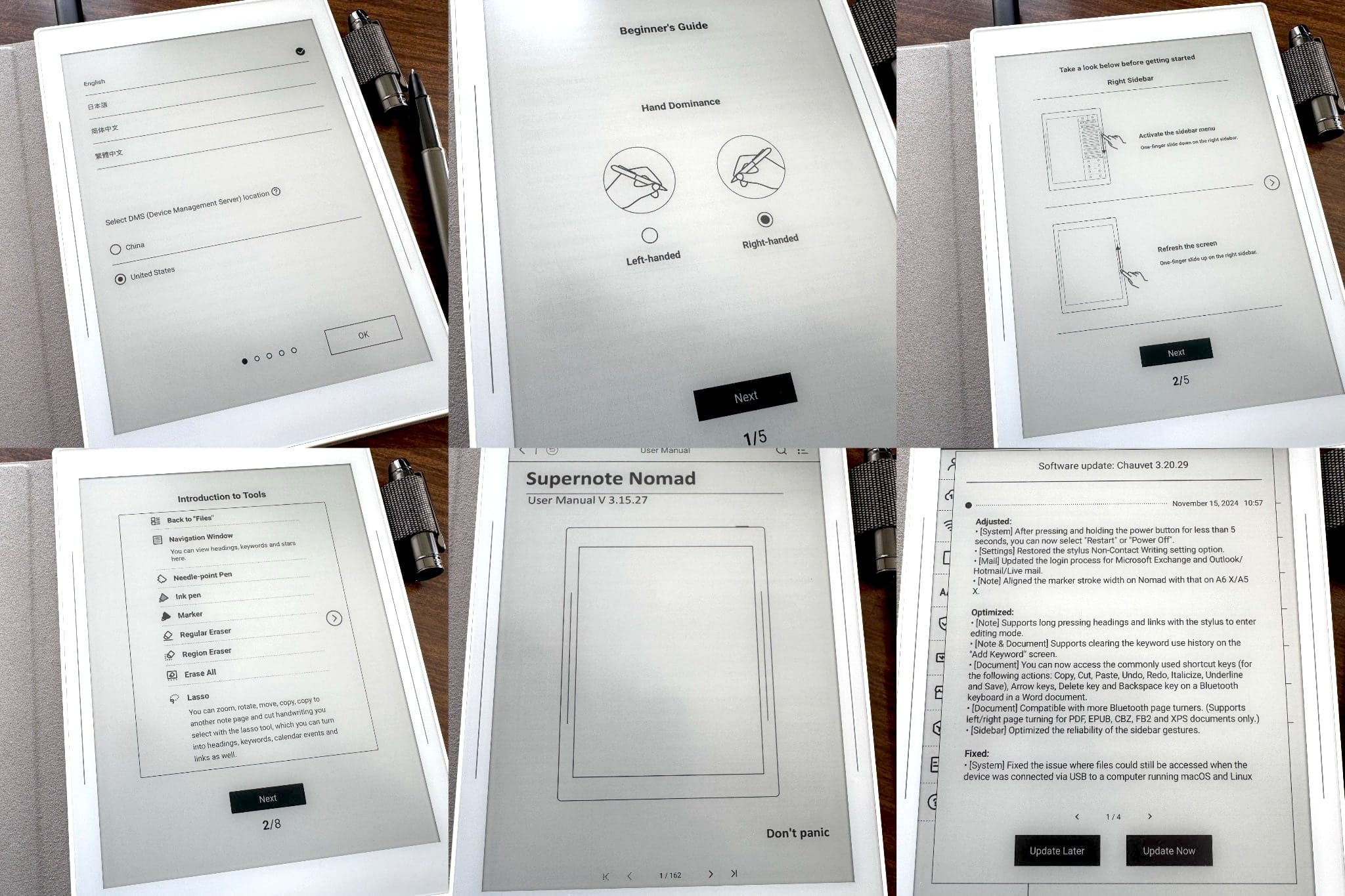

Going through the out-of-box setup experience was a good way to get an initial feel for the screen–it’s not as white as a “paperwhite” screen, but is very readable in daylight, although it can be a bit of a challenge to photograph.

This series of photos was taken with the same camera and lighting conditions and you can see there is a bit of variation, plus there is some glare from the writing layer (which isn’t noticeable in person) and my “reflection” on the bottom part of the screen:

This is a good time to mention that most of the rest of the photos in this post were processed to compensate for camera perspective. Even though they were taken in pairs under roughly the same lighting, I wanted to try to compensate for glare and reflections on camera, so all the shots had to be taken at an angle to the screen and would look awkward.

But one thing that is almost immediately noticeable if you’ve used other e-ink devices is that there is barely any shadow or inset from the frame–this is because the screen does not have a front light.

![[Nomad] thickness](/media/blog/2025/01/18/2335/wo0C4S9GDDpJzmzWNdlaRIyM6x0=/nomad_thickness.jpg)

The reason for that seems to be the desire to have the least possible amount of material between the pen and the screen–and in e-ink screens, the only way to add a reading light is to add enough of a layer for the light to propagate through.

Pen

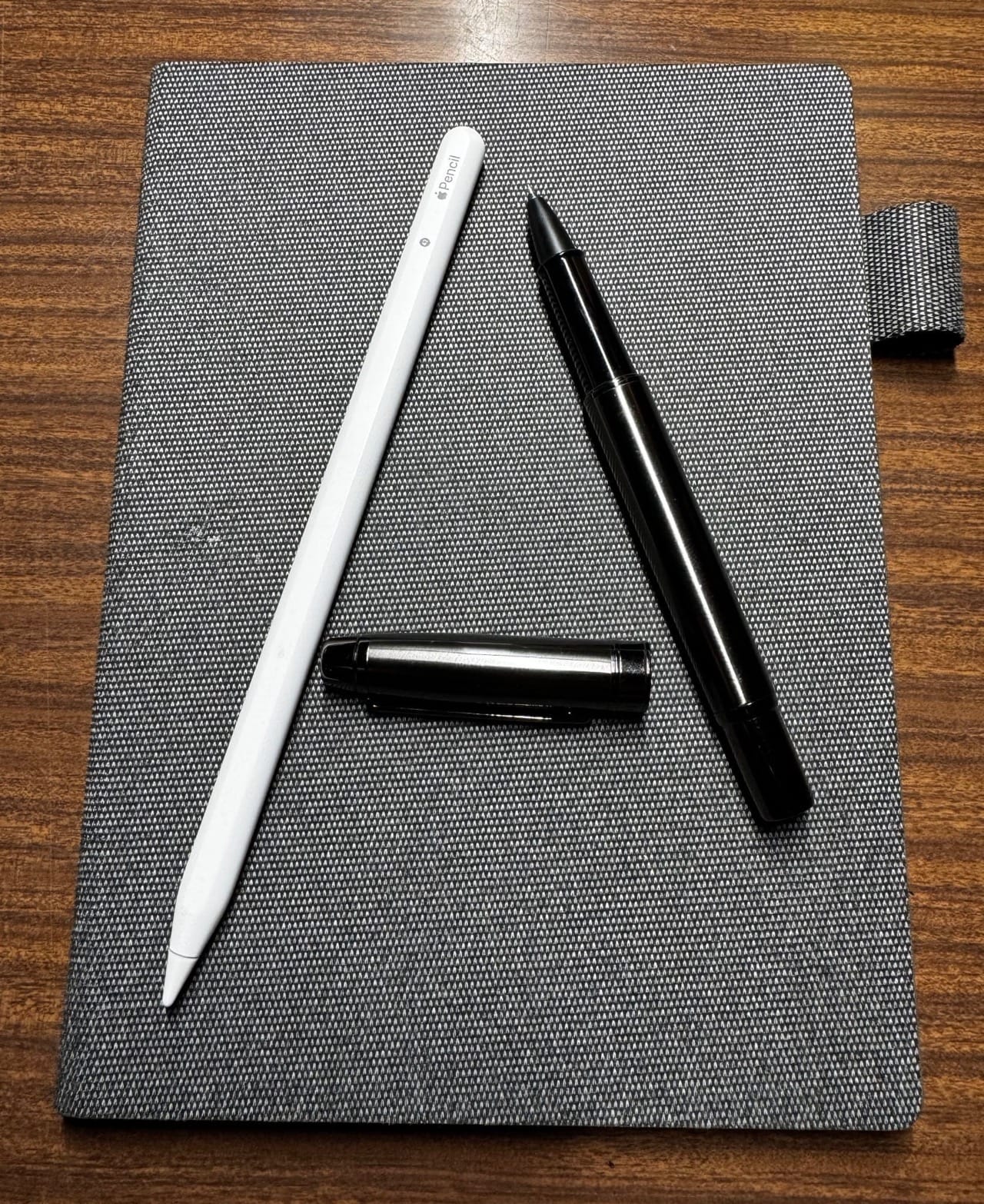

I originally wanted a LAMY pen (the Nomad supports its action button, which you can use to erase things) but that was out of stock, so I picked the impressively named Heart of Metal Pen in Samurai Black, which is surprisingly substantial.

Even though I quite like the modern Apple Pencil, the added thickness and weight distribution on the Samurai make it very pleasant to use, and the combination of the very slightly yielding tip and the subtle screen texturing made for a much nicer writing feel than the “paper-like” coverings I’ve been using on my iPads.

Software

The Nomad’s operating system is called Chauvet, and is effectively a heavily customized Android 11 system but to the point where there isn’t really any part of the UI that you would recognize as Android’s. There’s no home screen (just the sidebar icon box, which expands to full screen when you tap the More icon), no multitasking, and no distractions.

Everything else in the UI is both spartan and slick. Even with the constraints of e-ink, it was always intuitive and responsive, making it easy to navigate through notes and applications–except side-loaded ones, which tended to be a bit slower and less responsive.

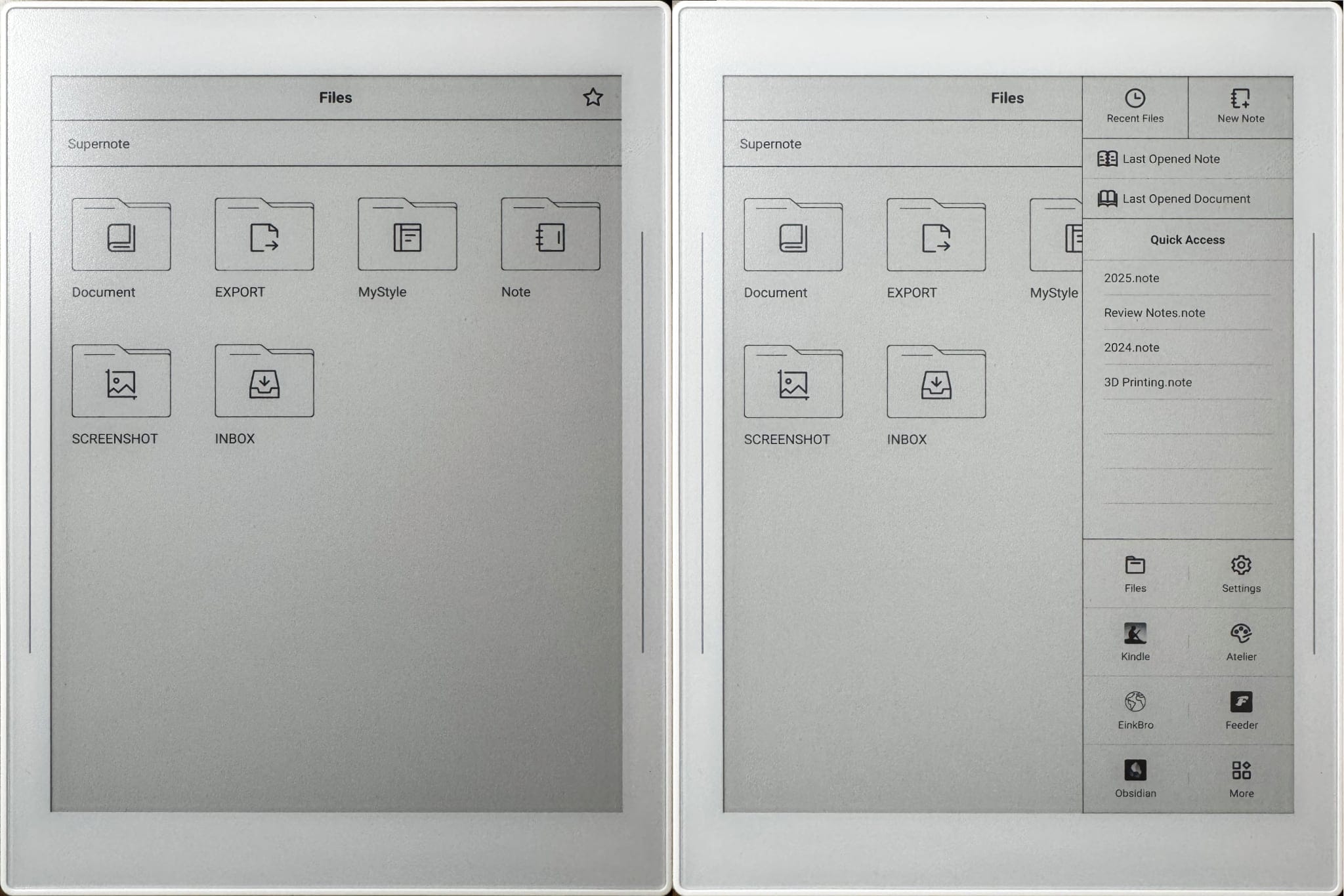

Files and Basic Navigation

The two lines that decorate the bezels also mark the location of the Nomad’s touch strips, which you can use with gesture controls to change pen/eraser behavior (on the left by default) and to swipe up or down to force a screen refresh or display the sidebar (on the right by default).

So when you swipe on the right, you open a quick access list for common actions, a list of your favorite files and the application tray:

Lock Screen

You can set a custom wallpaper for your lock screen, and that hides the only bit of the Android heritage that was noticeable to me several times a day–the Nomad can be locked with a six-digit PIN code, which you are prompted for whenever you open the folio, and that first input experience as you try to unlock the device doesn’t feel optimized at all–and is occasionally frustrating since it can actually take a while for the screen to update after you’ve tapped a digit.

I know that I am spoiled by the iPad’s lightning quick unlock experience, so I would love to see a fingerprint sensor on the Nomad, or at least an option for delayed locking so that shutting the folio for a few minutes doesn’t actually force me to muddle through the PIN entry. I also wonder if a pattern lock wouldn’t work much better–a couple of pen strokes and you’d be in.

Handwriting Experience

The primary input method is, unsurprisingly, freeform handwriting. You also have the option of an on-screen keyboard, and, of course, Bluetooth keyboards, but the hidden gem for me is that there is an Android handwriting “soft keyboard”:

This was a very pleasant surprise that is both reminiscent of how most Palm-era handhelds worked and so much better than the way than Scribble handwriting input works in iOS–where you essentially have to guess where you can set down the tip to write, and often have zero screen real estate to actually do so.

It has the same language support as “regular” note-taking, and the Nomad has built-in recognition for Chinese (both simplified and traditional), Japanese and US English, as well as the ability to download additional languages.

Portuguese handwriting recognition was OK (I honestly didn’t test it much, seeing as 99% of what I write is in English), but I should note that it was very fiddly to switch between languages (you need to make a several-tap trip back to Settings).

Chinese and Japanese handwriting recognition also seemed OK, although it’s been well over 15 years I wrote anything in any of those scripts and have no idea if stroke order helps. But since I am trying to learn a bit more Japanese, I intend to test this a fair bit more in the future.

A fly in the ointment was that the more languages I had active, the worse the soft keyboard recognition became (maybe because it also tries to present suggestions and takes up added CPU).

However, one thing that I found to be an odd omission is that there is apparently no way to integrate typed text with the Notes app–for instance, you cannot paste in text from other apps or even create a text box to type into, which feels like an odd omission since most other digital note taking solutions I used over the years let you mix handwriting and normal text (not always successfully–and I’m looking at you, OneNote).

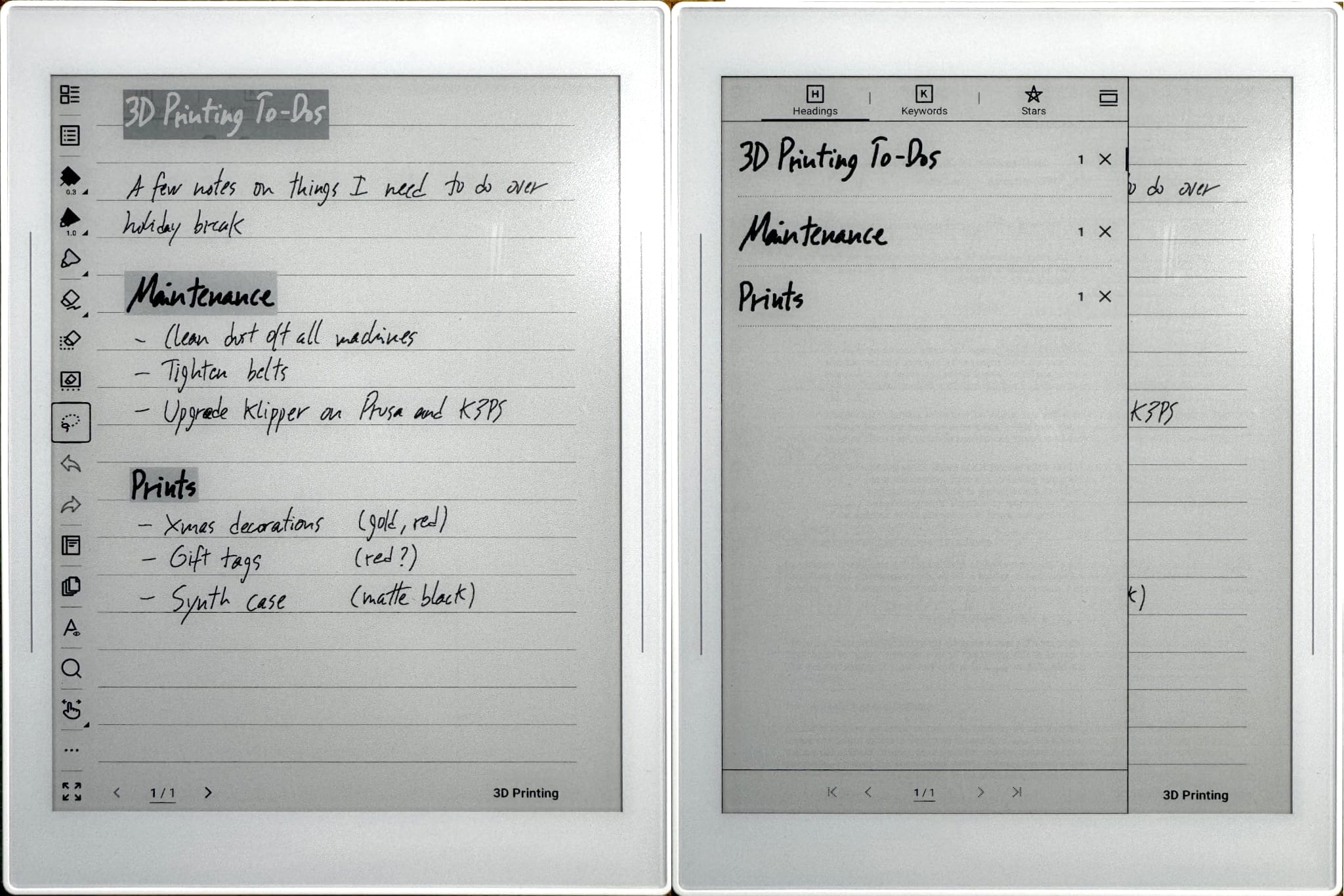

Managing Notes

The note-taking user experience is very much tied to how you manage your notes, and the first thing you’ll be prompted for when you create a note is a filename plus the “paper” template you want to use (there is an entire cottage industry out there around creating specific kinds of note-taking PDF and PNG templates, forms, and layouts for various activities, but I mostly went with the built-ins).

But the really neat thing is that you can turn your notes into a visual Wiki of sorts, with handwriting-centric tables of contents and navigation–when you select a handwritten word and mark it as a TOC entry, it is its handwritten version that is used in the UI, and you can link to that from other places:

This seems a trivial thing at first, but the combination of these things means that the visual layout of your notes and how you link between them becomes a lot more important than you might be used to (I certainly had to re-think the way I structure things a bit).

You can add pages to .note files (they’re effectively multi-page notebooks) and lasso handwritten text to copy/paste it between pages, so managing long-form is certainly doable, although it might take a little getting used to.

And while I researched what Python libraries there are out there to handle Supernote native formats, I found that there are lots of people doing “bullet journal” style note-taking and navigation, as well as various ways to manipulate, enhance and export notes independently (something I have yet to dabble in, although I did spot intriguing hints of Lua inside the files).

But the native way to export your notes is trivially easy and reassuring–you just export them out to .txt files and have your way with the result.

File Formats

Besides its own proprietary (but already somewhat reverse engineered) .note format, the Nomad supports PDF, EPUB, Word (.doc), Text (.txt), PNG, JPG, WebP, CBZ, FB2 and XPS (plus the Kindle app will open AZW3, MOBI, etc.), but, oddly, no Markdown.

The file manager refuses to recognize .md files as supported, which doesn’t prevent you from using Markdown in .txt files but will feel like an annoying limitation to pretty much every techie out there.

I get that regular people won’t know the difference between Markdown and a plain text file, but it was disappointing to have effectively zero ways to open a Markdown file on-device without renaming it.

A Tiny Word

The Nomad comes with a document editor called Word, which, true to expectations, opens .txt and creates .doc (not .docx) files you can open and continue editing on just about anything (Word, Pages, TextEdit, OpenOffice, etc.).

The .doc format is well-established enough that you can edit it seamlessly across different platforms (and edits on my Mac generally made it back, including some font and style changes), but Word has virtually no support for locally adding any kind of formatting beyond the very basic (you can do bold and italic with keyboard shortcuts, but that’s about it), and is probably best thought of as something you can use to clean up recognized text still on device.

Using it with a Bluetooth keyboard was straightforward, although I initially thought there were no formatting shortcuts—there are, but depending on the kind of keyboard you use, you might need to double-check how it’s configured. My cheap $20 foldable keyboard works great, but I had to set it to Windows mode to make Ctrl+B and Ctrl+I work.

Since there are no styles (only bold and italic), I ended up using Markdown hash marks and bold for headings, which was an acceptable compromise.

Screen updates while writing with a Bluetooth keyboard were fine–as you’d expect e-ink makes it a slower experience than when using a regular tablet (and, as a spoiler for later, it may be challenging to keep track of the caret in third-party apps), but I didn’t find it to be a real issue.

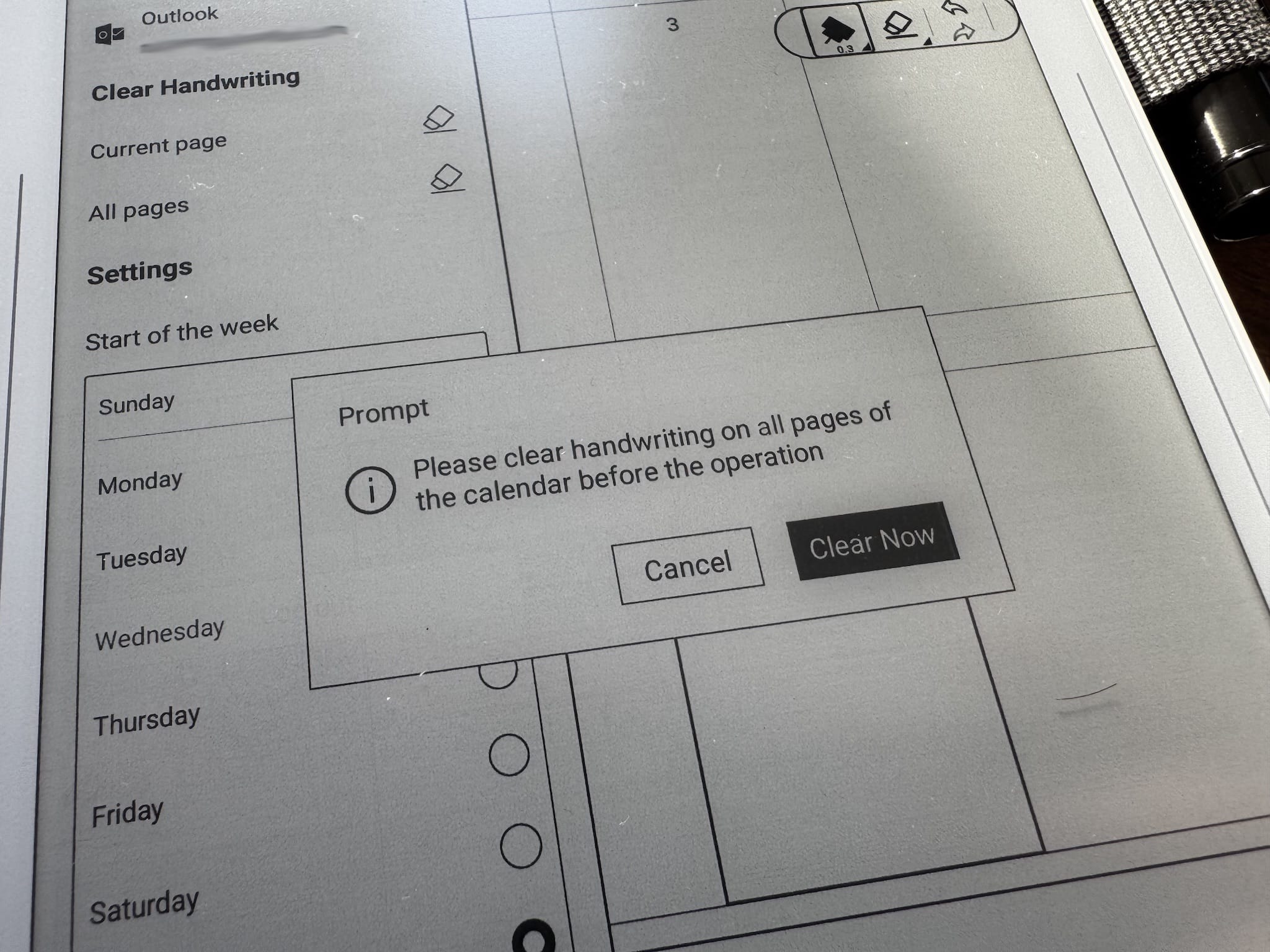

Calendar and To-Do

The calendar on the Nomad works very much like you’d expect it to–except that you can literally scrawl atop it, which is nice until you realize that the handwriting layer is “pinned” and that something as simple as changing the starting weekday completely invalidates the layout:

Notes that you individually add inside events do move around, but this was a bit disappointing–I’d expect the software to make an attempt at keeping annotations for each day in sync with the day itself regardless of its position in the layout.

That said, calendar syncing worked adequately, although like e-mail the calendar functionality is best thought of as a complement rather than a key feature.

However, to-do items apparently don’t sync with anything but the partner app, which is a bit of a let down (although to be honest the to-do app landscape is fraught with fragmentation, and most e-mail/cloud services don’t really support them properly).

This feels like something that needs a bit more work if you consider that one of the less obvious features of the Notes app is that you can create to-do items directly from it–and it would be nice to be able to sync them back to a “normal” calendar/to-do environment.

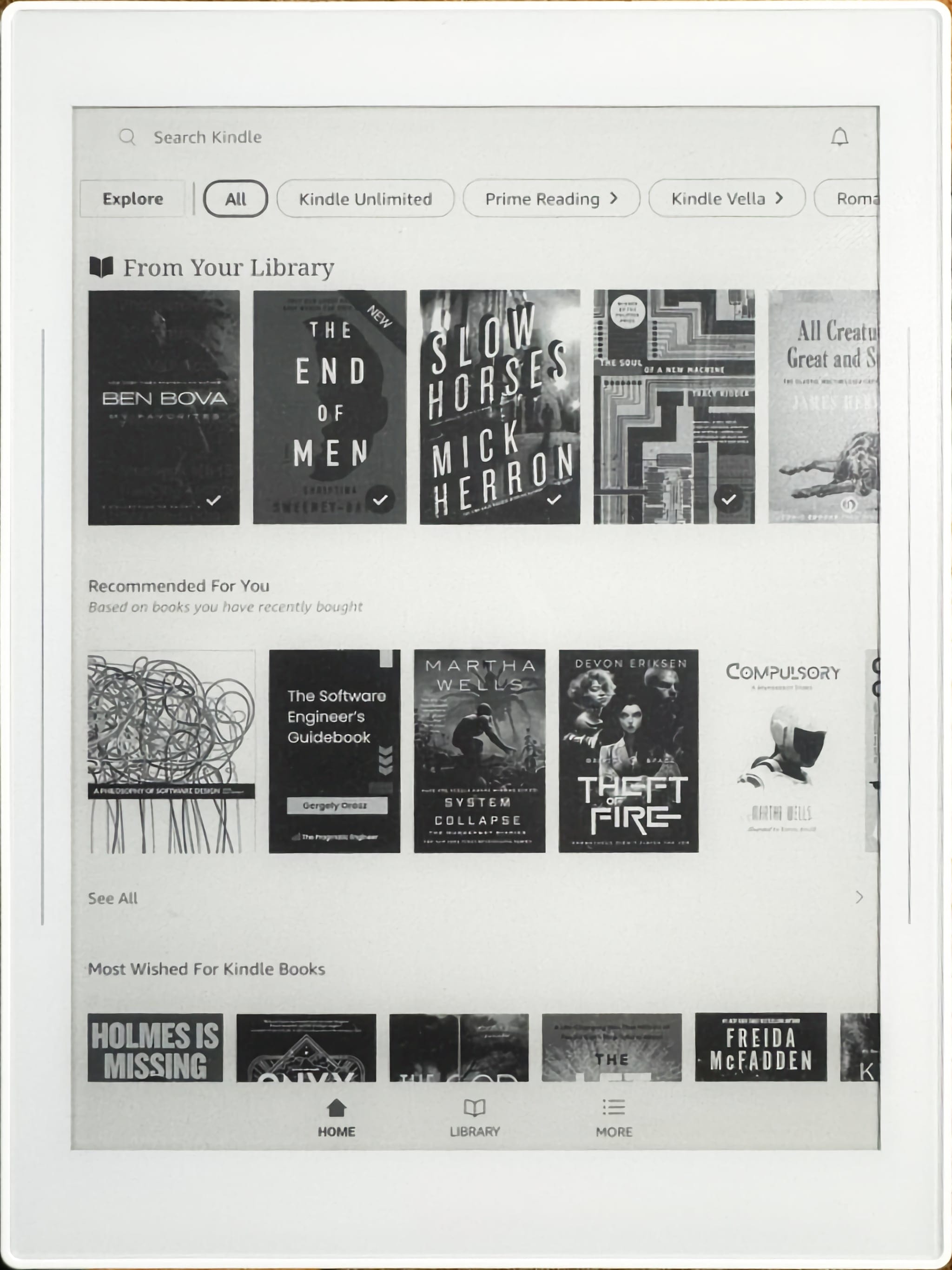

Kindle and PDFs

Up until now, my only way to (try) to read PDFs on a distraction-free device has been my Kindle, so that’s how I had my first go–with the unexpected side effect that after downloading the Kindle app via the Settings section of the Nomad, I ended up not picking up my Kindle again for the past two months, even considering that my Paperwhite has a very nice front light and the Nomad doesn’t.

The reason for that wasn’t that the Kindle app works spectacularly well on the Nomad–in fact, it feels a bit off because it might be optimized for e-ink, but it’s still an Android application first, and thus assumes it can try to do things like (simple, but slow) page animations. I also can’t annotate or integrate it with the Chauvet environment in any meaningful way (no way to share highlights, snippets, anything).

It was a much simpler reason–the screen, despite the lack of a front light, was surprisingly clear, readable, and larger, so the reading experience with my bedside light was still slightly more pleasant for me than on the Kindle, and the only real annoyance has been that I occasionally need to force a full screen refresh because the Android rendering surface gets messed up.

As to PDFs, I soon gave up on the Kindle app and started using the Nomad’s built-in viewer, which can save markup and highlight in a small (invisible) sidecar file as well as collecting snippets and notes in a little app called Digest (that I haven’t fully explored yet).

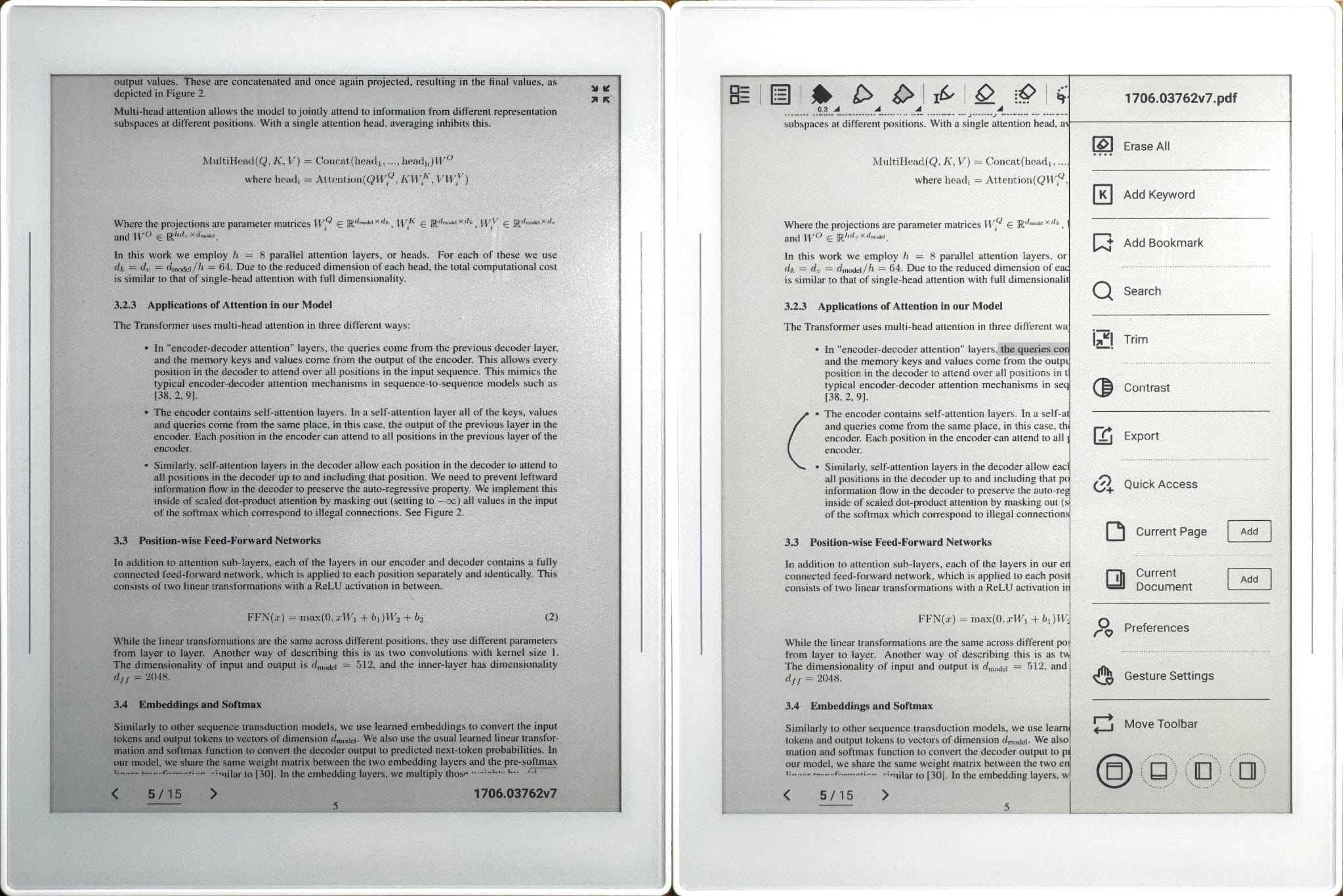

I have literally dozens of papers on my iPad that I have been meaning to well and truly study, but I never get around to it there due to distractions–an e-ink device is perfect, albeit the Nomad’s screen is still a tad small for me:

And if you have comic books in PDF or .cbz format this is the way to go, since it has contrast controls and a simple but effective trimming feature to reduce margins:

Atelier

Besides the Kindle app, this is the only other app you can download from inside the internal “store”, and it is a nice bitmap-oriented drawing app with pencil, pen, marker and even a rather quaint spray tool that allows for creative expression (it has pressure support) and quick sketches.

And I was quite surprised to realize that besides being able to select and transform (resize, skew and rotate) strokes, it also supports multiple layers and exporting to either transparent or regular (white background) PNGs.

Interestingly, drawing seems to actually be performed at twice the physical resolution of the screen (you can zoom out to 50%, and I exported out a 2808 × 3744 image), which means you can do some very fine sketching indeed – I saw some very artistic things in r/supernote, and I intend to try my hand at some sketching when I do some traveling with the Nomad.

The actual e-ink drawing experience feels responsive and natural enough, but one thing Atelier highlighted for me is that despite being able to manipulate portions of my pathetic attempts at sketching in various ways, the Nomad actually lacks a way to do diagrams–by which I mean vector-oriented, technical diagrams with geometric shapes. This isn’t the focus of Atelier, but it feels like a missing feature if, like me, you spend a lot of time doing tech.

I dug around a bit and found that most of my gripes are actually roadmap items on their public Trello, so I’ll be tracking those. In the meantime, I just drew simple diagrams inside the Notes app, and only popped back into Atelier to try to sketch out a bigger, more detailed one–only to realize there was no obvious way to copy/paste it directly into a note.

Connectivity

The Nomad supports Supernote Cloud, Dropbox, Google Drive and OneDrive out of the box, with a companion app that syncs via Supernote Cloud.

I didn’t use the companion app at all, since it looked like I really had to set up an account and I honestly have far too many online accounts already–I’ve been on a quest to cut down on them, and fortunately the Nomad provides many more options.

OneDrive and Dropbox

I started out by connecting my personal Microsoft account to the Nomad (which also synced my e-mail and calendars), but this approach turned out to make the entirety of my OneDrive accessible to the Nomad, and since I didn’t like the all-or-nothing approach, I switched to Dropbox (which, despite its foibles, has a much saner application access model where each external application only sees its own folder tree).

Dropbox syncing worked OK, although I found it a bit slow and on a couple of occasions PDF and EPUB files added in Dropbox didn’t sync back to the Nomad upon the next manual sync. However, I soon found easier and quicker ways (for me) to get my content in and out of the Nomad.

Direct Access

To me, that turned out to be the Nomad’s built-in web server, which I could use without any hassles or additional apps from my Mac, Linux or iPad–and that was more than enough to get at exported files and upload both EPUB and PDFs for testing.

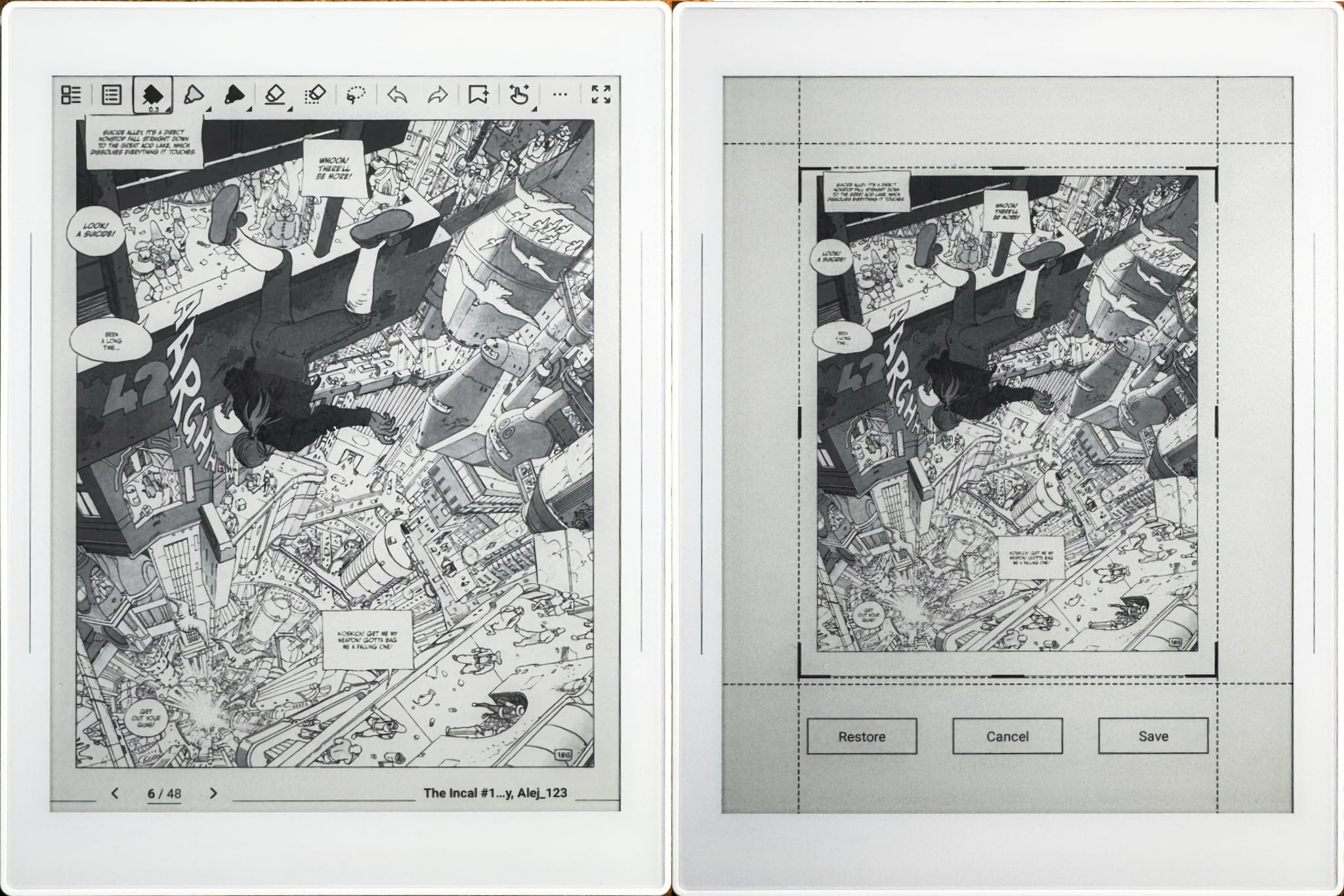

And it goes a bit further: by pulling down on the top of the screen, you can tap either of two options to turn on a built-in web server that will let you browse your Nomad and transfer files in either direction, or (and this was the most fun) mirror your screen:

You can then share your browser over Teams or Zoom, which makes for a pretty great whiteboard experience. I could see myself using it daily if the Nomad had any sort of built-in diagramming tools, but I guess we’ll have to wait.

Sideloading

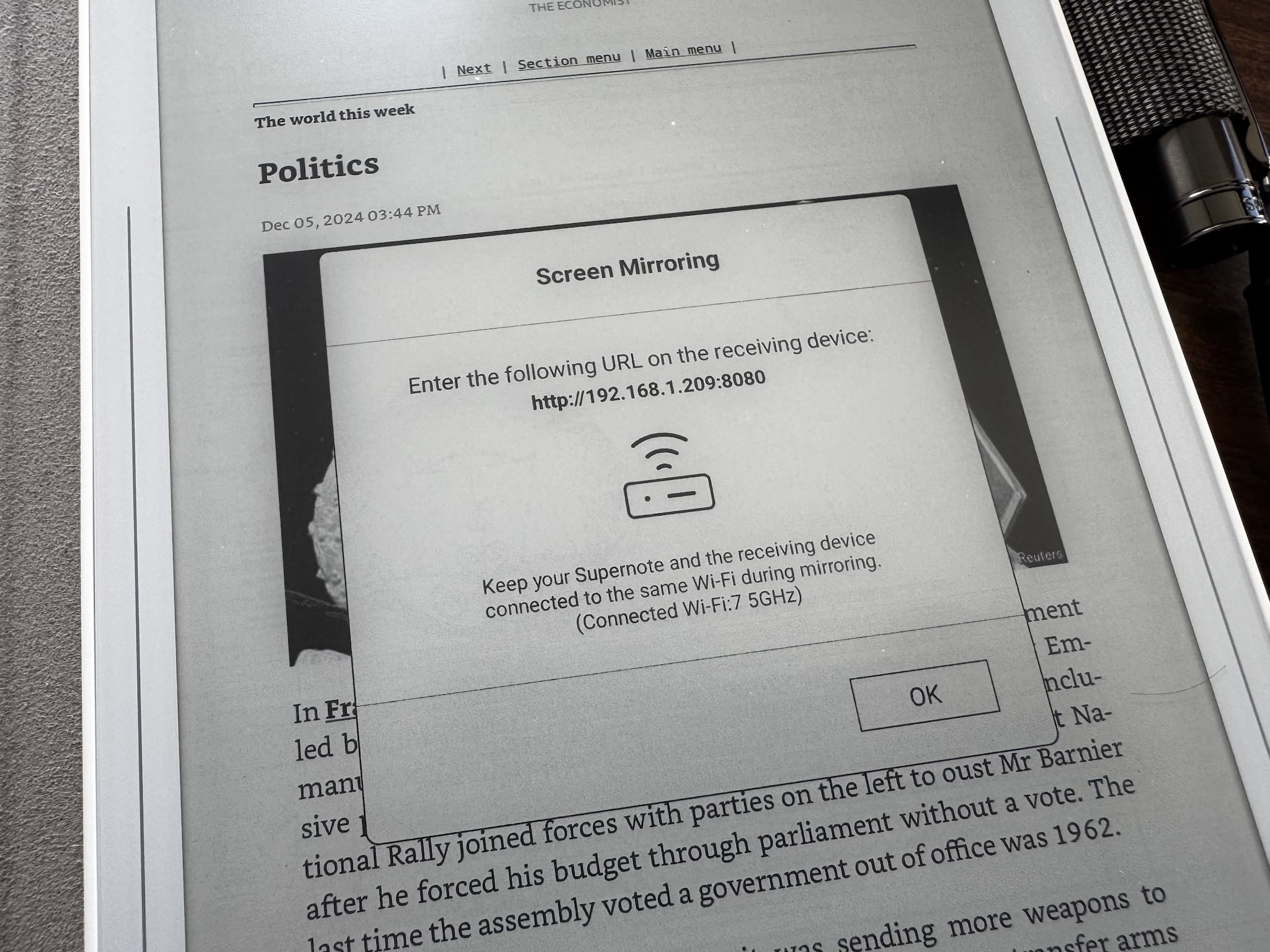

Of course, being who I am, one of the very first things I did was explore sideloading–I just enabled it in Settings, hooked up a USB cable and installed F-Droid, through which I then installed Syncthing, KoReader, Organic Maps, EInkBro, Termux, Voice (an audiobook app, which worked well with Bluetooth earbuds) and Feeder (a very nice RSS reader) with zero issues.

EInkBro has a great unsung feature (saving EPUB files) that comes in really handy on the Nomad, and is nicer than the built-in browser (which I haven’t mentioned because, by design, you can’t even add it to the sidebar).

This was my undoing, as I spent a lot of time trying things out instead of exploring the Nomad’s native features. And before you ask, yes, you can run Termux just fine and connect to other machines using ssh, although you shouldn’t expect a magical terminal experience on an e-ink display.

But if, like me, writing longform in vim is your jam, yes, you can also do that too, and you will be pretty happy with it as long as you have a Bluetooth keyboard and tweak the font settings a bit.

The Obsidian Elephant In The Room

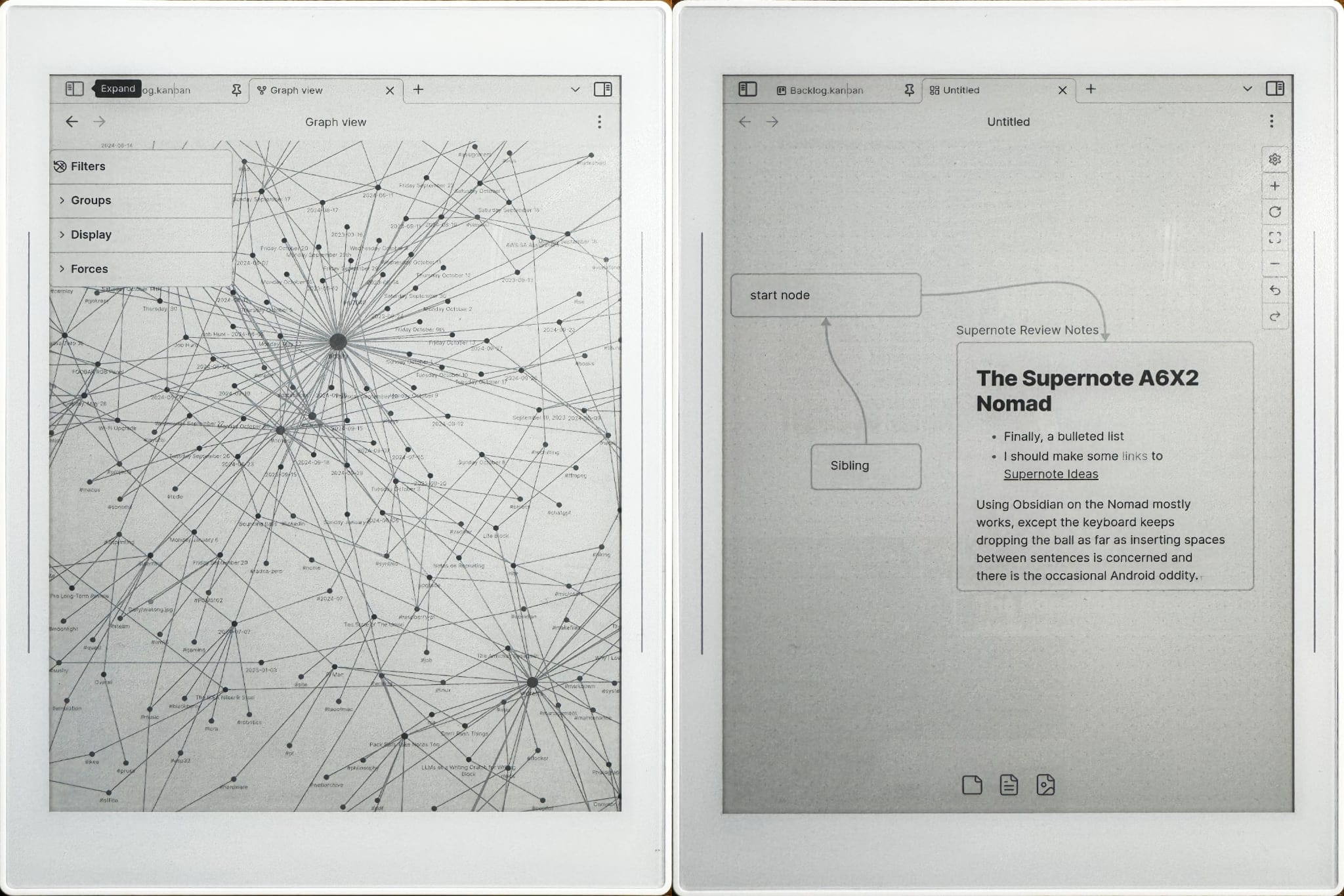

Although I am still not a fan of Obsidian itself on the desktop, there are far too many people using it to ignore the fact that you can, indeed, sideload it into the Nomad.

And one of the reasons it took me a bit long to write up my Nomad experience is that I completely nerd-sniped myself by installing Obsidian on it. That profoundly changes the note-taking experience on the Nomad if, like me, all your writing is stored in a folder tree of Markdown files.

I won’t beat about the bush: It can be a little slow (Obsidian isn’t the slickest of Android apps to begin with, and is definitely not e-ink optimized), but using it on the Nomad felt like letting in a Trojan horse:

And yes, it was a game changer in the way I am using the Nomad–even though it has basically zero integration with the Chauvet environment, handwriting notes and then eventually moving them into Obsidian worked beautifully for me, although I cannot use any of the nice native note linking features.

But I was able to create and edit most of this post in the Nomad alone, using either the handwriting “keyboard” or a Bluetooth one.

Other than Android screen refresh and file handling oddities the experience was surprisingly good, only let down by the fact that the handwriting keyboard’s quirks (like its constant refusal to insert a space between new sentences and the odd pause or mis-recognized word) often came to the fore.

I later installed Syncthing to get the data across to my Mac, and with a judicious combination of plugins I now have most of my current notes, post drafts, a bunch of Mermaid diagrams and even a Kanban board on my Nomad, which effectively means that it has become the second device I reach for every morning.

But you need to remember that the Nomad was not really designed for this–and that shows sometimes, although when compared to my limited experience with the Remarkable, I’d say the Nomad is a much more flexible device.

Replacing My iPad?

One of the things I wanted to understand was if the Nomad could replace my iPad mini, which is still the first device I pick up every day and often the last I put down.

The short version is: almost, but it isn’t really meant to.

I can use Feeder to read my news over breakfast, and in a pinch I could also check my e-mail and calendar, but I use the iPad for fundamentally different things–not just news (and media) consumption, but also reading e-mail across several accounts, managing multiple calendars, flicking through various web front-ends (like the Proxmox console) and doing several non-iPad-typical things like logging in to remote machines and coding.

But the fact that I now pick up both the iPad mini and the Nomad when I saunter to the kitchen to get breakfast should tell you something–they’re both roughly the same size, and their functionalities are effectively complementary; I now often scribble notes on the Nomad instead of the iPad, and leave the iPad behind when I go into the office since I am now using the Nomad to jot down notes during the day.

Oh, and you’ll notice I haven’t mentioned battery life–the Nomad trounces any iPad regarding that (I feel like I charge less than once a week), but that was a given going into this.

A Word About AI

There is none. No cloud services, no ChatGPT, no “smart” features other than the built-in, fully on-device handwriting recognition, which is perfect as far as I’m concerned.

The Nomad is a device that is very much about you and the way you write your notes without any “aids”, and that’s it–but you can sideload a chat app if you want.

Conclusion

The Supernote Nomad hasn’t replaced my iPad mini (I don’t think anything ever will except another iPad), but it has pretty much completely replaced my Kindle and had a measurable impact on the way I take notes and write.

I think it’s the perfect e-ink device given its size If you primarily take notes during meetings or need something to use on the go, with the caveat that I have had limited experience with anything but a Remarkable I got on loan during last year’s troubled Summer.

And yes, the software is very much fine-tuned for handwriting–perhaps a bit too much from my perspective given the lack of Markdown/better rich text formatting and some kind of diagramming features, but then again I don’t think of this as a notebook; I know it is an Android device, and as such I have rather fuzzy expectations of it.

But for non-technical people or people who want to completely ignore that part (which, sadly, I couldn’t thanks to Obsidian), it is surprisingly flexible and intuitive.

And if you take that view, then things like Atelier and the possibility of creating a completely handwritten “visual Wiki” become much more interesting.

In one of my handwritten notes, I summarized the pluses and minuses as follows:

Pluses

- I love the Nomad’s analog feel and the way it forces me to mind my handwriting

- Anything that can read my chicken scrawl is to be commended.

- That, in turn, requires additional focus and forethought when writing, which ultimately leads to clearer and more organized thoughts.

- Even after only two months, it’s already had a sizable influence on the way I write.

- The handwriting “soft keyboard” is great.

- Sideloading and Obsidian are just icing on the cake.

Minuses

- The inability to copy plain text from anywhere and intersperse it with handwritten notes feels like a missed opportunity.

- I would really like to see a way to do architecture diagrams or even a basic vector editor with snap to grid.

- The handwriting keyboard is still a little buggy, dropping the ball as far as automatically inserting spaces between new sentences is concerned.

- Reading PDFs on the Nomad is still quite challenging due to the screen size (zooming and panning is still easier on the iPad, but I don’t like reading PDFs there).

This last point is the only one that has zero bearing on software–for me, reading and annotating PDFs isn’t really a software issue, it’s a physical matter that simply requires more screen real estate to avoid fiddling with zoom settings and to be immersive enough to be satisfactory.

So like me, if you occasionally have to read PDFs (or are a student and want to annotate textbooks), you should probably look at the newly released Manta instead.

But if you’re on the road frequently or need a handy, portable notebook for meetings, journaling or the odd bit of sketching, I’d say the Nomad is definitely something to look into.

Next Steps

Me, I’ll certainly be using it for the foreseeable future, and I’ll be sure to update this post if I find any more interesting things to say about it–I will at the very least try to post a more in-depth follow-up on what I’m figuring out about the data formats and internals and how I’m using it with Obsidian in a few months.

After all, it wouldn’t be me if I didn’t try to push the envelope a bit.