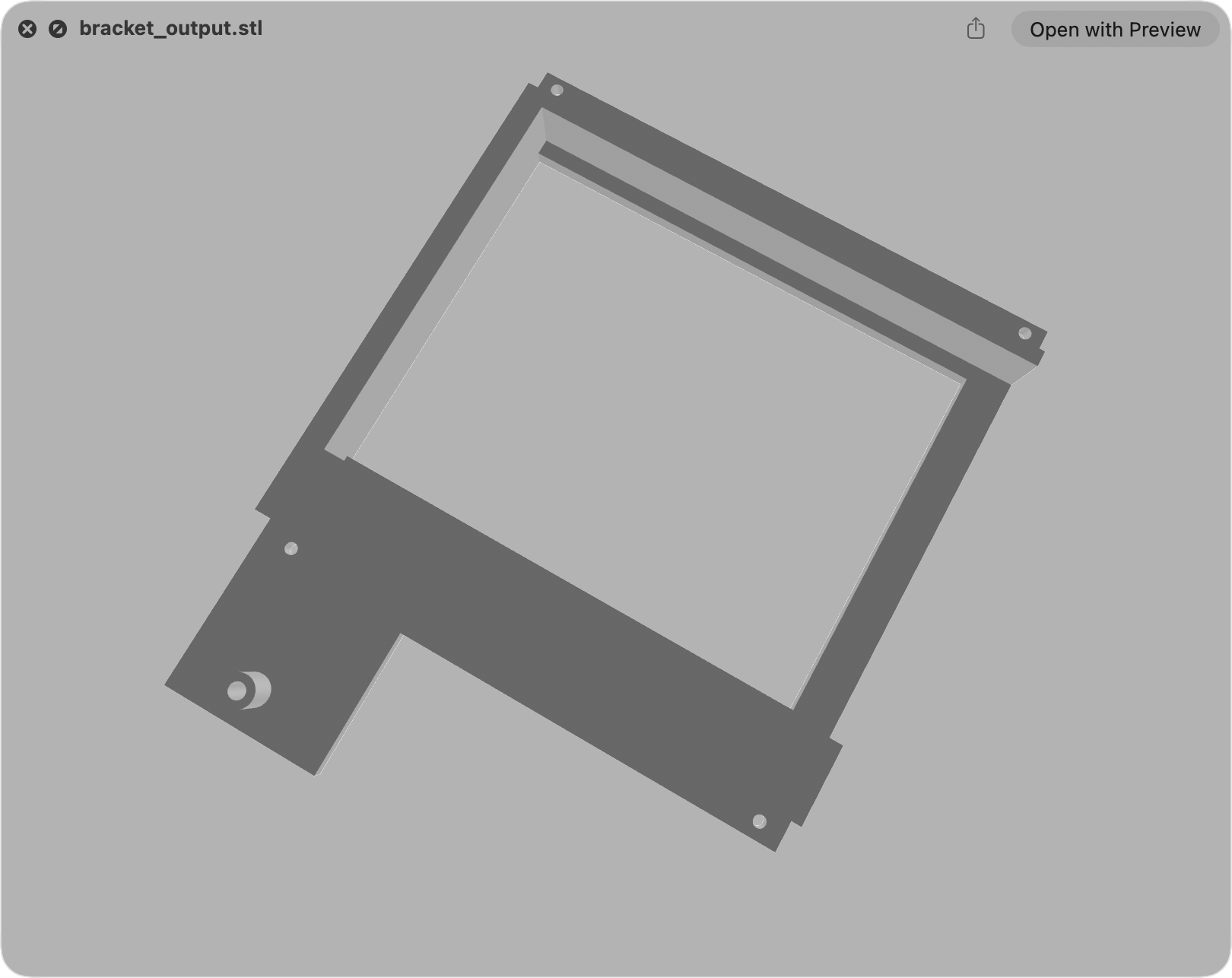

So, I finally got around to opening the Maclock I’ve had sitting around for a while, and I was looking at the STL files for the screen bracket that are over on Printables.

Since I want to fit a lot more electronics into the case, one of the things I need to do is modify that bracket a bit so I can actually use the brightness knob to drive a potentiometer instead of just a dummy knob.

But you can’t really edit STL files, and I don’t have the original CAD files, so I thought “well, maybe I can just ask an LLM to reverse-engineer the STL into an OpenSCAD file, and then I can modify that”.

So I created a SPEC.md file with the following content, spun up a new agentbox container to handle it, and gave it to pi:

# STL to OpenScad reconstruction

You are running inside a Debian system with sudo, brew, python3 and whatever you need to accomplish this task.

Your job is to take the STL file in this workspace and reconstruct a copy of it using OpenSCAD.

If the STL is too large or complex, you can try decimating it/using octrees/segmenting it/using marching cubes as needed.

## Requirements

- The final STL file must be within 0.1mm accuracy of the original

- The OpenSCAD code must be modular, readable, and have relevant constants surfaced at the beginning for a customizer

- You should focus on building reusable tools, not one-off scripts

- You should maintain a plan.md file with your progress checklist and tick off items (including failed approaches) as you make progress

Much to my surprise, Claude Opus 4.6 was able to handle this task pretty well, and it produced a stupefyingly accurate OpenSCAD file:

// WonderMac Screen Bracket - OpenSCAD Reconstruction

// Reconstructed from STL analysis

// All dimensions in mm

/* [Main Dimensions] */

// Total width of the bracket (X direction)

bracket_width = 68; // X: -50 to 18

// X offset (left edge position)

bracket_x_offset = -50;

/* [Back Plate] */

// Height of the tall vertical back plate

back_plate_height = 21.5; // Z: 0 to 21.5

// Thickness of the back plate (Y direction)

back_plate_thickness = 2; // Y: -16.5 to -14.5

// Y position of back plate inner edge

back_plate_y = -16.5;

/* [Top Shelf] */

// Bridge depth (connects back plate to top lip)

bridge_depth = 5.5; // Y: -14.5 to -9

// Bridge height

bridge_height = 2; // Z: 0 to 2

// Top lip depth

top_lip_depth = 2; // Y: -9 to -7

// Top lip height

top_lip_height = 5; // Z: 0 to 5

/* [Frame] */

// Frame outer Y bounds

frame_outer_y_min = -66.5;

frame_outer_y_max = -14.5; // matches back plate

// Frame inner bounds (lower section Z=0-7)

frame_inner_x_min = -47;

frame_inner_x_max_lower = 18; // open right side

frame_inner_y_min_lower = -64.5;

frame_inner_y_max_lower = -16.5;

// Frame inner bounds (upper section Z=7-9)

frame_inner_x_max_upper = 13;

frame_inner_y_min_upper = -62.5;

frame_inner_y_max_upper = -17.5;

// Frame heights

frame_lower_height = 7; // Z: 0 to 7

frame_upper_height = 2; // Z: 7 to 9

/* [Bottom Lip] */

// Lip extension below frame

lip_y_min = -70.5;

lip_y_max = -66.5;

lip_z_min = 3;

lip_z_max = 5;

lip_height = 2; // lip_z_max - lip_z_min

/* [Extended Plate] */

// L-shaped plate at Z=5-7

plate_z_min = 5;

plate_z_max = 7;

plate_height = 2;

// Bottom part of L (full width)

plate_bottom_y_min = -9;

plate_bottom_y_max = -3;

// Left part of L (extends upward)

plate_left_y_max = 15;

plate_left_x_max = -30;

/* [Screw Post] */

// Cylindrical post with through-hole

post_center_x = -41;

post_center_y = 10.5;

post_outer_radius = 2;

post_inner_radius = 1;

post_z_min = 0.5;

post_z_max = 5; // meets plate bottom

/* [Screw Holes] */

// Hole radius for mounting holes

mount_hole_radius = 0.75;

// Lip mounting holes

lip_hole_left_x = -47.75;

lip_hole_right_x = 15.75;

lip_hole_y = -69;

// Plate mounting holes

plate_hole_left_x = -46;

plate_hole_right_x = 15;

plate_hole_y = -5;

/* [Resolution] */

$fn = 64;

// ============================================

// Modules

// ============================================

module back_plate() {

translate([bracket_x_offset, back_plate_y, 0])

cube([bracket_width, back_plate_thickness, back_plate_height]);

}

module bridge() {

translate([bracket_x_offset, back_plate_y + back_plate_thickness, 0])

cube([bracket_width, bridge_depth, bridge_height]);

}

module top_lip() {

translate([bracket_x_offset, -9, 0])

cube([bracket_width, top_lip_depth, top_lip_height]);

}

module frame_lower() {

difference() {

// Outer rectangle

translate([bracket_x_offset, frame_outer_y_min, 0])

cube([bracket_width,

frame_outer_y_max - frame_outer_y_min,

frame_lower_height]);

// Inner cutout

translate([frame_inner_x_min, frame_inner_y_min_lower, -1])

cube([frame_inner_x_max_lower - frame_inner_x_min,

frame_inner_y_max_lower - frame_inner_y_min_lower,

frame_lower_height + 2]);

}

}

module frame_upper() {

difference() {

// Outer rectangle (same as lower)

translate([bracket_x_offset, frame_outer_y_min, frame_lower_height])

cube([bracket_width,

frame_outer_y_max - frame_outer_y_min,

frame_upper_height]);

// Inner cutout (smaller = thicker walls)

translate([frame_inner_x_min, frame_inner_y_min_upper, frame_lower_height - 1])

cube([frame_inner_x_max_upper - frame_inner_x_min,

frame_inner_y_max_upper - frame_inner_y_min_upper,

frame_upper_height + 2]);

}

}

module bottom_lip() {

translate([bracket_x_offset, lip_y_min, lip_z_min])

cube([bracket_width, lip_y_max - lip_y_min, lip_height]);

}

module extended_plate() {

// Bottom part of L (full width, Y=-9 to -3)

translate([bracket_x_offset, plate_bottom_y_min, plate_z_min])

cube([bracket_width,

plate_bottom_y_max - plate_bottom_y_min,

plate_height]);

// Left part of L (Y=-3 to 15, X=-50 to -30)

translate([bracket_x_offset, plate_bottom_y_max, plate_z_min])

cube([plate_left_x_max - bracket_x_offset,

plate_left_y_max - plate_bottom_y_max,

plate_height]);

}

module screw_post() {

translate([post_center_x, post_center_y, post_z_min])

cylinder(r=post_outer_radius, h=post_z_max - post_z_min);

}

module screw_post_hole() {

translate([post_center_x, post_center_y, -1])

cylinder(r=post_inner_radius, h=back_plate_height + 2);

}

module lip_holes() {

// Left lip hole

translate([lip_hole_left_x, lip_hole_y, lip_z_min - 1])

cylinder(r=mount_hole_radius, h=lip_height + 2);

// Right lip hole

translate([lip_hole_right_x, lip_hole_y, lip_z_min - 1])

cylinder(r=mount_hole_radius, h=lip_height + 2);

}

module plate_holes() {

// Left plate hole

translate([plate_hole_left_x, plate_hole_y, plate_z_min - 1])

cylinder(r=mount_hole_radius, h=plate_height + 2);

// Right plate hole

translate([plate_hole_right_x, plate_hole_y, plate_z_min - 1])

cylinder(r=mount_hole_radius, h=plate_height + 2);

}

// ============================================

// Assembly

// ============================================

module bracket_assembly() {

difference() {

union() {

back_plate();

bridge();

top_lip();

frame_lower();

frame_upper();

bottom_lip();

extended_plate();

screw_post();

}

// Subtract all holes

screw_post_hole();

lip_holes();

plate_holes();

}

}

bracket_assembly();

But what is more important is that I was able to capture the entire process in a SKILL.md file, and it makes for an amazing read:

# SKILL: STL to Parametric OpenSCAD Reconstruction

## Goal

Reverse-engineer a binary/ASCII STL mesh file into a clean, parametric OpenSCAD source file that reproduces the original geometry within a specified tolerance (e.g. 0.1mm Hausdorff distance).

## When to Use

- You have an STL file of a mechanical part and need an editable parametric source

- The part is primarily composed of prismatic (box-like) and cylindrical features — not organic/sculpted shapes

- You need the output to be human-readable and customizable, not just a mesh re-export

## Prerequisites

- **Python packages**: `numpy`, `trimesh`, `scipy`, `shapely`, `networkx`, `rtree`, `numpy-stl`

- **System packages**: `openscad`

- Install with: `pip3 install numpy trimesh scipy shapely networkx rtree numpy-stl` and `sudo apt-get install openscad`

## High-Level Approach

### Phase 1: Mesh Triage

Load the STL with `trimesh` and gather key statistics to understand the scope:

- **Vertex/face count**: Determines complexity. Under ~5k faces is likely a machined/printed part with clean geometry.

- **Bounding box and extents**: Gives the overall dimensions.

- **Volume and watertightness**: Confirms the mesh is valid and closed.

- **Euler number**: Computes genus (number of through-holes). Formula: `genus = (2 - euler_number) / 2`. This tells you how many holes to find.

### Phase 2: Identify Z-Level Structure

For prismatic parts (brackets, enclosures, mounts), the geometry is almost always built from features extruded along one principal axis. Identify which axis that is by examining the unique coordinate values of vertices.

1. **Find unique vertex coordinates** along each axis (rounded to ~3 decimal places). The axis with the fewest unique values is the extrusion/stacking axis.

2. **List the discrete levels** on that axis. For this bracket, Z had only 8 unique values: `[0, 0.5, 2, 3, 5, 7, 9, 21.5]`. Each pair of adjacent levels defines a "layer" of constant cross-section.

3. **Count up-facing and down-facing face areas** at each level. Up-facing faces at a Z-level mark the *top* of a feature; down-facing faces mark the *bottom* of a feature starting at that height. The area values serve as checksums for your reconstruction.

### Phase 3: Cross-Section Analysis

Take planar cross-sections at the midpoint of each layer using `trimesh.section()`:

1. **Slice the mesh** at each intermediate Z value (e.g. Z=0.25, Z=1, Z=2.5, etc.).

2. **Convert to 2D polygons** via `section.to_planar()` and examine the `polygons_full` property.

3. **Simplify polygons** with Shapely's `.simplify()` to reduce curved arcs to key vertices while preserving corners.

4. **Transform back to world coordinates** using the planar transform matrix to get actual XY positions.

5. **Record each polygon's exterior and interior (hole) boundaries**. Note how many vertices remain after simplification — a 5-point polygon is a rectangle, a 9-point polygon is an L-shape, a 17-point polygon is a circle approximation, etc.

Track how the cross-section *changes* between layers — this reveals where features start, end, merge, or split.

### Phase 4: Identify Geometric Primitives

From the cross-section data, decompose the shape into CSG primitives:

- **Rectangles** (5 simplified vertices = box cross-section): Record corner coordinates, extrusion height range.

- **L-shapes / U-shapes** (9+ vertices): Decompose into union of rectangles, or model as rectangle-minus-rectangle.

- **Circles / arcs** (17+ vertices after simplification): Compute center as midpoint of extremes, radius as half the span. Verify by checking vertex distances from the computed center — they should all equal the radius.

- **Rings/annuli** (polygon with circular hole): Outer and inner radius from the exterior and interior boundaries.

For each primitive, determine:

- XY bounds or center+radius

- Z range (which layers it spans)

- Whether it's additive (part of the union) or subtractive (a hole to difference out)

### Phase 5: Cross-Validate with Vertex Grouping

For extra confidence, directly examine the raw vertices at each Z-level:

- Group vertices by their Z coordinate.

- For levels with few vertices (≤20), print them all — these directly reveal rectangle corners.

- For levels with many vertices, look for clusters. Compute distances from suspected circle centers and verify constant radius.

- Check that circle parameters (center, radius) are consistent across multiple Z-levels.

### Phase 6: Build the OpenSCAD Model

Structure the `.scad` file for readability and customization:

1. **Constants at the top** in OpenSCAD Customizer sections (`/* [Section Name] */`). Every dimension gets a named variable with a comment showing its physical meaning and original coordinate range.

2. **One module per feature**: `back_plate()`, `frame_lower()`, `screw_post()`, `lip_holes()`, etc. Each module is self-contained and uses only the global constants.

3. **Assembly module**: A single `bracket_assembly()` module that `union()`s all additive features, then `difference()`s all holes. This keeps the boolean logic clean and makes it easy to toggle features.

4. **Resolution control**: A single `$fn` parameter controls circle smoothness globally.

Modeling patterns:

- **Rectangular frame**: `difference()` of outer `cube()` minus inner `cube()`.

- **L-shaped plate**: `union()` of two overlapping `cube()` calls.

- **Through-hole**: `cylinder()` with height extending past the material (add 1mm on each side with `-1` offset and `+2` height to ensure clean boolean cuts).

- **Ring/post**: `cylinder()` for the outer, with a through `cylinder()` subtracted.

### Phase 7: Render and Compare

1. **Render** with `openscad -o output.stl model.scad`.

2. **Compare** using a reusable Python comparison tool that computes:

- **Bidirectional surface distance**: Sample 50k points on each surface, find nearest point on the other surface using `trimesh.nearest.on_surface()`. Report mean, max, 95th/99th percentile.

- **Volume difference**: Compare `mesh.volume` values.

- **Bounds match**: Check bounding boxes agree within tolerance.

- **Topology match**: Compare Euler numbers.

3. **Iterate** if the Hausdorff distance exceeds the tolerance. Common fixes:

- Wrong dimension by a small amount → re-examine vertex coordinates at that Z-level

- Missing feature → look at the worst-mismatch sample points to locate the problem area

- Circle approximation error → increase `$fn`

### Phase 8: Verify the Accuracy Target

The final gate is the bidirectional Hausdorff distance. For this task the target was 0.1mm; the achieved result was 0.004mm (25× better than required). The residual error comes entirely from polygon approximation of circles (`$fn=64` gives a theoretical max error of `r × (1 - cos(π/64))` ≈ 0.0024mm for r=2mm).

## Key Lessons

1. **Z-level analysis is the critical insight for prismatic parts.** If the mesh has only a handful of unique Z values, the part is a stack of extruded profiles and can be exactly decomposed.

2. **Cross-sections + simplification finds the primitives fast.** Shapely's `simplify()` with a small tolerance (0.05–0.1mm) collapses arcs to their key points while preserving sharp corners.

3. **Euler number tells you how many holes to find.** Don't stop looking for features until you can account for all `(2 - χ) / 2` topological handles.

4. **Face normal grouping separates flat vs. curved surfaces.** Axis-aligned normals (±X, ±Y, ±Z) are planar faces; all others are cylinder walls. The Z-component of non-axis normals reveals whether cylinders are vertical (Z=0) or angled.

5. **Up/down face area sums serve as checksums.** Compute the expected area of each horizontal surface from your model parameters and verify it matches the STL. This catches dimension errors before rendering.

6. **Model in original coordinates, not relocated.** Keeping the STL's native coordinate system avoids translation errors and makes comparison trivial.

7. **Build the comparison tool first.** A reusable `compare_stl.py` with surface sampling and Hausdorff distance makes iteration fast and objective.

## Reusable Tools

All tools live in `tools/` with CLI interfaces, `--help`, and `--json` output.

See `tools/README.md` for full usage.

| Tool | Phase | Purpose |

|------|-------|---------|

| `tools/stl_info.py` | 1 | Mesh triage: stats, topology, genus, components |

| `tools/stl_zlevel.py` | 2 | Find discrete height levels, face areas, vertex coords |

| `tools/stl_cross_section.py` | 3–4 | Slice mesh, extract & classify 2D polygons |

| `tools/stl_normals.py` | 4 | Face normal grouping, cylinder feature detection |

| `tools/compare_stl.py` | 7 | Bidirectional Hausdorff distance, volume, topology |

### Quick-start workflow

python3 tools/stl_info.py part.stl # What am I dealing with?

python3 tools/stl_zlevel.py part.stl --vertices # Layer structure + corners

python3 tools/stl_cross_section.py part.stl # Auto-slice cross-sections

python3 tools/stl_normals.py part.stl # Find cylinders and holes

python3 tools/stl_cross_section.py part.stl --axis x --at 0 # Hidden internal features

# ... write OpenSCAD model ...

openscad -o output.stl model.scad

python3 tools/compare_stl.py part.stl output.stl # Verify accuracy

## Deliverables

| File | Purpose |

|------|---------|

| `tools/` | Reusable analysis toolkit (see `tools/README.md`) |

| `bracket.scad` | Parametric OpenSCAD source with customizer sections |

| `bracket_output.stl` | Rendered STL for comparison |

| `plan.md` | Progress checklist with identified components and results |

…and yes, it also created tools for its own use. It’s not a chimpanzee using a stick to get at termites, but it is pretty close: it’s an LLM creating its own toolchain to get at the underlying geometry of a mesh.

This is far more sophisticated than I expected, and it shows that LLMs can be used for scoped reverse-engineering tasks with the right prompting and constraints–but it also shows that you need to be able to understand the problem domain and guide the model with the right structure and checks to get a usable result.

The caveat is that this is a very specific use case (STL to OpenSCAD for prismatic parts), and I wouldn’t expect the same approach to work for more complex shapes or different file formats without significant adjustments. But it’s very much above and beyond what we could do a year ago.

Now excuse me while I go and give it a development board’s dimensions and ask it to design a custom case for it…